What you need to know about tapering antidepressants

- Behroz Dehdari

- Aug 28, 2025

- 14 min read

For many years, I have helped patients reduce or completely stop taking their psychotropic medications. For the past year, I have been doing it full-time in private practice. Together with six other colleagues, I have reviewed large parts of the existing research on tapering antidepressants and written a review article that will soon be published in Läkartidningen. In connection with lectures on tapering at the Swedish Psychiatric Congress and the National Congress of General Practitioners, I have also had the opportunity to exchange experiences with several colleagues. Below I summarize what I know about tapering.

Is it really that hard to stop taking antidepressants?

First of all, it should be pointed out that there is a lot we do not know. Furthermore, the degree of discomfort varies considerably between different people. Some who try to quit can do so without any problems whatsoever. However, a significant proportion experience withdrawal symptoms of varying severity. For many, it will be bearable, albeit very unpleasant, while others experience so much discomfort that continued tapering seems impossible.

Withdrawal symptoms are very similar to those experienced when starting antidepressants: increased anxiety, fatigue, dizziness, sleep disturbances, headaches and sweating. Other common symptoms include a feeling of unreality, tingling in the hands and feet and emotional instability.

The symptoms can affect anyone and it is therefore not a “certain type” of patients who experience withdrawal symptoms. For example, I have met a patient who told me that he abruptly stopped both snus and alcohol after many years of use, but he could not stop taking antidepressants. The longer someone has been on antidepressants, the more likely it is that tapering off will be difficult. The onset of withdrawal symptoms should therefore be interpreted as a biological phenomenon, in all likelihood caused by the brain needing to find a new equilibrium when the dose of antidepressants is reduced.

However, psychological factors can affect the intensity and course. A typical example is if the patient is told by their doctor that “the disease has returned”. This will of course scare the patient and the symptoms may be intensified. Another way is if they are told that withdrawal will be extremely difficult and that the symptoms may be signs of brain damage.

Many of my clients tell me that their previous doctors did not seem to understand the discomfort they experienced during the tapering process. Either they thought the symptoms were exaggerated or that their presence only showed that they should stay on the medication, even though the patients themselves expressed that they strongly felt that it was related to the discontinuation. This lack of understanding can greatly worsen the discomfort.

Withdrawal symptoms usually appear on the second or third day after changing the dose and usually last between one and three weeks (this depends to some extent on the half-life of the preparation). However, sometimes the symptoms can last considerably longer than that, especially if you have reduced the dose too much. If it becomes so troublesome that you cannot stand it, it is wise to increase the dose again to the previous dose, stay there until you feel better and then reduce it again to a slightly smaller dose.

With the right support, most people who are motivated to taper their antidepressants are likely to be able to do so, despite varying degrees of discomfort. The chance of success increases if you have somehow managed the problems or resolved the difficulties you had that were the reason you started taking the tablets in the first place. It increases further if the tapering is done slowly and in small steps at a time.

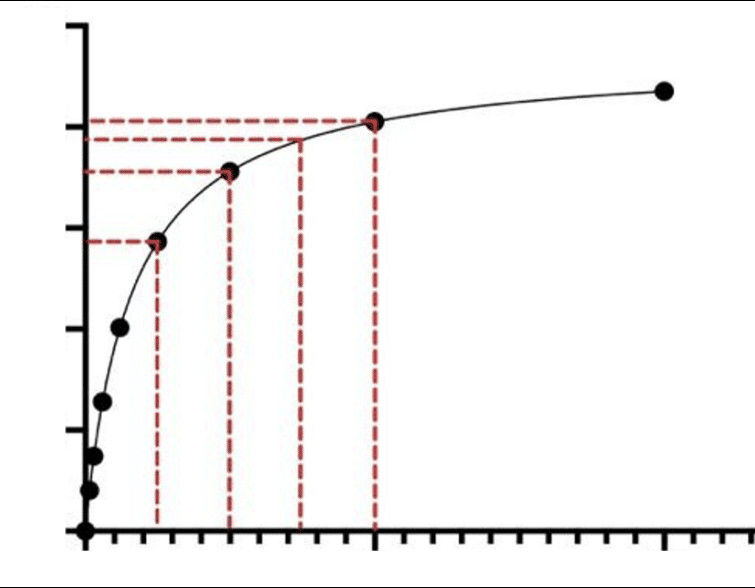

Theoretically, it seems wise to also follow the so-called hyperbolic curve. This curve describes the relationship between the dose of a substance and the degree of influence on its binding site (usually a reuptake pump). The relationship is not linear: a dose twice as high does not give a double effect. Even at low doses, a high proportion of the pumps are blocked.

In the picture above we see what happens if you taper off by the same amount each time, in this case by 12.5 mg from the starting dose of 50 mg (dashed line on the far right). At this dose, approximately 80% of the reuptake pumps are blocked. As we begin to taper, there are no major changes on the y-axis. However, there is a very large jump in the last step from 12.5 mg to 0. There, the impact on the transporters drops from approximately 60% to 0%.

If we assume that withdrawal symptoms occur because the brain needs to find a new equilibrium, it seems reasonable to instead taper down in equal steps with respect to the y-axis, that is, with respect to the effect on the binding site of the drug. If we continue to use sertraline as an example and wish to reduce by a quarter each time with respect to the y-axis, we can reduce from 50 mg to about 15 mg, then to 6 mg and finally to 2 mg. The challenge will be to arrange these small doses because they cannot be purchased at the pharmacy.

There are several options here: many tablets can be crushed, dissolved in water and drawn up with a syringe. Some preparations are available in oral solution. Others are available in smaller strengths in so-called ex tempore preparations. In addition, there is a pharmacy in the Netherlands that can manufacture most preparations in small strengths pre-packaged in sachets. Here is a blog post where I list the most common preparations and the alternative strengths in which they are available.

What you should know is that the hyperbolic curve does not describe the relationship between dose and clinical “effect”. It is therefore important to distinguish between the effect on the reuptake pump and what then happens “downstream”, that is, after serotonin has bound to its receptor. In addition, chemical signal transmission is extremely complex and involves a lot of other neurotransmitters.

Furthermore, it should be noted that there is no randomized controlled study yet that supports that a hyperbolic taper would be better than a linear taper, but with smaller steps than previously recommended. In any case, it is an advantage to stick to a method that you believe in.

Are you sick if you are depressed or have anxiety?

What a psychiatric illness or mental disorder is has been hotly debated for decades. I have written about this here. The basic idea is that it should be a deviation, either from the usual or from the desirable. The DSM, the diagnostic manual that is often called the bible of psychiatry, also states that it must involve either suffering or impairment and be due to a dysfunction in the body's natural functions.

Muscle soreness can be said to be a deviation from what is desirable and can involve both suffering and functional impairment. But muscle soreness is not due to a dysfunction in the body, on the contrary, and is therefore not a disease. In the same way, many of the mental conditions that we currently medicate for are not diseases.

The DSM also states that if the symptoms can be considered an expected response to a stressor, the condition should not be considered a disorder. The question is, how much one “has” to suffer or how great one’s functional impairment can be before a doctor considers it a disease. There are no blood tests, no brain X-rays or other objective markers.

The vast majority of people I have met in psychiatry have reacted quite normally to what they have experienced. The more “serious” the diagnosis, the harder it has been for them. In many cases, the triggering stressor may not have been particularly remarkable in itself, but in light of the patient's entire life history, it can be seen that it has triggered a so-called overdetermined crisis . Such a crisis triggers or reinforces previously unresolved wounds in the individual. Others say that since childhood they have been taught to push away negative emotions. In adulthood, they have difficulty correctly identifying that they actually feel sad and hurt about something - instead, this is expressed in feelings such as anger, depression or anxiety.

However, it may still make sense to talk about illnesses in some cases, even though the individual has reacted in an expected way. These would in that case be very deep depressions, psychotic deliriums, manias and severe catatonia. However, these conditions are rare. The boundary between what can be considered normal human functioning and what should be considered pathological is poorly illuminated.

Instead, the prevailing picture today is that all psychiatric diagnoses stand for different diseases in the brain. This is despite the fact that diagnoses are by definition only descriptions and not explanations. They are intended as tools for communication and cannot say anything at all about what your symptoms are due to. So you do not have concentration difficulties or difficulty being on time because of your ADHD diagnosis. On the contrary, you have been diagnosed with ADHD because you exhibit these difficulties. People who have difficulty stopping drinking alcohol do not do so because they have a diagnosis of alcohol dependence and they are not depressed or think life is meaningless because of depression. Using the diagnosis as a way of explaining symptoms is just circular reasoning and equivalent to saying that the reason you have a headache is because you have a headache.

The fact that antidepressants can help is no argument that the drugs cure a chemical imbalance. Alvedon can relieve pain from both muscle aches and ear infections, but these conditions are not due to an alvedon deficiency and one of them is not a disease to begin with.

What do antidepressants do and what happens when you reduce the dose?

There is debate about what antidepressants actually do. When you ask patients themselves, many say they get “thicker skin”, “like armor” or that "negative thoughts do not stick as much". For many, this is a huge relief, especially at first, and some have told me that the tablets have been life-saving, that they have increased the threshold for experiencing negative emotions and thoughts, when nothing else has helped.

When you then reduce the dose of antidepressants, the threshold is lowered again. If you have a similar life situation to before you started taking these drugs, it is of course reasonable that you will feel more anxiety again. But it also seems that the threshold temporarily drops even lower than it was before. That is, even stimuli that previously did not cause anxiety (or dizziness and other symptoms) can do so during withdrawal. Many describe it as an easily aroused irritation that they do not recognize. We can call this “chemical anxiety”. There is no need for psychological interpretation here, that is, the chemical anxiety does not stand for anything in life, it is simply due to the brain's balance being upset. What matters is to endure, engage in meaningful activities and remind yourself that it will pass.

As I wrote above, withdrawal symptoms usually go away within three weeks, but can last longer if the reduction has been too great. How long is currently debated. Some say it can last several months, or even several years. The term PAWS, post acute withdrawal syndrome, has been coined for this condition.

However, it is important to distinguish between symptoms caused by withdrawal and symptoms that are due to one's previous way of reacting now having come to the fore again. If one has been on these drugs for many years, one's emotional range and way of reacting have been affected for a long time. Now that this is changing, one needs to find new ways to regulate one's emotions. This is another thing that speaks in favor of a slow tapering, without the symptoms themselves needing to be directly linked to withdrawal.

In addition, there is a danger in interpreting all the problems that arise during the tapering process as withdrawal symptoms. It is common to experience discomfort. Several studies have noted that over a two-week period, approximately 30% of a normal population experiences one or more of the following symptoms: fatigue, aches, difficulty concentrating, difficulty sleeping, sexual difficulties, anxiety or dizziness. That is, problems that could have been interpreted as withdrawal symptoms.

However, some experience very clear physical symptoms - or symptoms that they did not have before - long after tapering. I have clients who have experienced clear withdrawal symptoms beginning a few days after tapering and persisting for several months. The incidence of PAWS is currently unclear. There is probably a connection with having tapered off too quickly several times. It is speculated that then a phenomenon called kindling may occur, which can, simplified, be understood as a hypersensitivity reaction in the brain.

Regardless of the exact mechanism of action, some patients experience discomfort long after tapering off. This is important information for anyone considering starting the tablets. It is also something that any doctor who extends a prescription for antidepressants without meeting their patient should consider.

What can be done to increase the chances of success?

Even if you taper off in small steps and follow the hyperbolic curve, you may experience withdrawal symptoms. With good support, these can usually be tolerated. Physical exercise, spending time in nature, contact with other people and animals, cold baths, meditation/relaxation exercises, cultural experiences or something else that feels meaningful to do usually helps.

Going to therapy, or just having an empathetic listener to talk to, increases the chance of successfully tapering off and also reduces the risk of having to start medication again. However, my experiences speak strongly against the image that depression is a lifelong illness that you have to take medication for the rest of your life.

It can be counterproductive to focus on what symptoms may occur during tapering. I therefore do not use checklists to regularly monitor what withdrawal symptoms my clients experience, this only increases the focus on discomfort. The goal should be to live as normal a life as possible, a life where you focus on what you can do, and not on what limits you.

Are all psychotropic drugs bad?

Although I believe that psychotropic drugs are overused and have significantly more serious side effects than is generally known, I am not completely against them. Nor do I believe that antidepressants are just placebos. It is true that the difference in effect, assessed as points on various rating scales, is minimal compared to placebo. But this does not necessarily mean that antidepressants and placebos are identical in all respects. In my private practice, I have rarely had to use diagnoses, but I do sometimes prescribe psychotropic drugs. In that case, I use the drug-centered model of drugs, and not the disease-centered one . The latter claims that the drugs “attack” or cure specific diseases. The drug-centered model instead believes that the drugs have certain effects that can be used.

Antidepressants, for example, seem to reduce the brain's readiness to interpret stimuli in a way that leads to anxiety. So I do not believe that antidepressants correct a chemical imbalance in the brain in the "disease" of depression. This chemical imbalance has not yet been found for any psychiatric diagnosis, whether for depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or ADHD. Our medications are not "magic bullets" that attack diseased areas of the brain, they do not work like antibiotics. What they do is instead induce a different mental state than the one you were in before. A state that is hopefully preferable. As I mentioned above, I have met many patients who have told me that the tablets have been life-saving or in any case have helped them to have a bearable life when nothing else has worked. This applies not only to antidepressants but also to neuroleptics, lithium and central stimulants.

Can it be harmful to be on antidepressants?

The danger of using antidepressants as a cover for our emotions, however, is that we do not learn to interpret and productively manage our emotions. The evolutionary point of emotions is precisely that they should guide our thoughts and our behavior. Anxiety can be a signal that something is not right. If we chemically dampen this signal, the problem will remain, but what has happened is that we no longer care about it.

Here one could argue that some types of anxiety are simply not a signal of something “underlying”. For example, a wasp phobia does not necessarily have to camouflage an internal conflict but may have arisen after an individual was nearly killed by a wasp sting. One could also argue that some conflicts may not be manageable at the moment, precisely because they create so much anxiety, and that antidepressants lead to the anxiety level becoming manageable.

It is therefore obvious that the question of whether someone should start taking antidepressants requires a very careful review of the person's entire life situation, and is not something that any doctor, regardless of experience, can decide after just a few minutes.

The second danger is that antidepressants not only make it harder to feel negative emotions, but also affect positive emotions. My clients repeatedly tell me that life feels a little greyer than before. Things are not as fun as before they started taking the pills. Sexual desire is often affected, sometimes completely gone, sensitivity in the genitals has decreased (an effect that has been known for a long time and where some men even use antidepressants when needed, when they experience problems with premature ejaculation). Many say that they generally have more difficulty getting in touch with their emotions, that they live in a glass bubble. Some are unsure whether they love their partners or their children.

The third danger concerns long-term physical side effects. Most antidepressants cause increased appetite, which leads to weight gain with an increased risk of metabolic diseases. There is also now data indicating that the risk of bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract increases. Women who wish to become pregnant should be made aware that there is an increased risk that the fetus will experience withdrawal symptoms such as difficulties with both breastfeeding and breathing. There is also data indicating that the newborn has a slightly increased risk of increased blood pressure in the lungs, which is associated with increased mortality.

The fourth danger is precisely what we are discussing: it can be very difficult to stop taking them.

How long should the tapering be?

I advise anyone who has been on antidepressants for more than about 6 months not to stop them abruptly, from one day to the next. In 2025, a meta-analysis was published, written by 20 researchers. The conclusion was that tapering off antidepressants does not, in principle, give rise to withdrawal symptoms at all. The meta-analysis included studies in which patients had either started on antidepressants or received placebo. Then they tapered off and compared both groups. It turned out that those who tapered off antidepressants had only one more symptom on the so-called DESS scale (Discontinuation Emergent Signs and Symptoms) than those who had received placebo. The researchers concluded that the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms was not clinically significant and thus seems to contradict everything I have written above.

What the researchers (many of whom have financial ties to pharmaceutical companies) unfortunately did not disclose was that the study participants in the meta-analysis had only been on antidepressants for a few weeks. In six of the studies, for only eight weeks; in four studies, for 12 weeks; and in one study, for 26 weeks. Of course, no conclusion can be drawn from this about how difficult it can be after several years.

In any case, I have taken the longest study in the meta-analysis - which was 6 months - into account in my recommendation that tapering is probably not necessary if you have only been on antidepressants for a shorter period of time. This is also in line with my and many colleagues' clinical experience. However, if you have been on the drugs for a longer period of time, I recommend a well-considered tapering.

I would say that if it has been more than 6 months but less than a year, it is usually possible to taper relatively quickly, often in 3-5 weeks. If it has been more than a year but less than two years, my recommendation is to taper in about 3-4 months. If it has been longer than two years, the tapering usually needs to be extended even more. I have some clients who have been on antidepressants for 20 years or more, where it is not unusual for a tapering period of 1-3 years, or even longer. I repeat that these are only general indications and do not serve as medical advice.

Summary

Tapering off antidepressants can cause withdrawal symptoms.

For some, the symptoms become very troublesome and persistent. Others cope with it without any major problems at all.

The emergence of anxiety, fatigue or depression during the tapering period should not be interpreted as a return of the "disease".

It is generally wise to taper off much more slowly than previously recommended. Often, you will need to use much smaller doses than are available for purchase.

With the right support, most people are able to taper off their antidepressants.

It is my hope that this post can help patients get the right care when they want to stop taking their pills. We doctors need to get better at tapering but also at using antidepressants for the right indication. It is actually not that difficult: what is most important is that we take the time to really listen to what our patients are saying. Unfortunately, the trend seems to be going the other way.

Comments